At certain points in life and work, we all need to perform under pressure. The problem is, many people think that performing under pressure is a gift – that some people have it, and some people don’t. It’s not always easy, but performing under pressure is a skill that you can improve. In this article, you can learn more about the physiological and psychological components which underpin performance under pressure, and discover five steps that you can take to prepare to perform at your best, whatever life throws at you.

Beyond stress management

Stress management is a hot topic, for good reason. Most of the time, stress management refers to reducing stress, but this only represents one part a more significant theme that underpins almost every aspect of human wellbeing and performance. That theme is ‘self-regulation’, which describes your ability to monitor and adjust your physiological and emotional states according to your situation and environment.

In some cases, this adjustment may require you to down-regulate how stressed or excited you are. For example, if you were about to speak in an important meeting, but were too nervous to articulate your thoughts clearly, you may need to find a way to:

a) Down-regulate your physiological state, by slowing your breathing, to speak in complete, evenly paced sentences

b) Change your emotional state by choosing to focus on the process of delivery, rather than being concerned about how that delivery may be perceived by the audience.

In other situations, you may need to up-regulate your level of stimulation and excitement. For example, if you felt distracted and lethargic before an important presentation, you may need to:

a) Up-regulate your physiological state, by moving more, to increase your heart rate.

b) Change your emotional state, by reminding yourself of why the presentation is important, to both you and your audience.

Adapting to whatever situation you find yourself in

While it’s understandable to bias our thinking toward stress reduction, in the context of performing under pressure I think it’s more helpful to consider ‘optimal activation’. Optimal activation represents a range in which we have the ideal physiological and emotional mix for whatever situation we are facing. Optimal activation varies according to differences between individuals and conditions, so we need to develop a toolkit to find this optimal activation state more quickly and consistently.

Physiological and emotional states are closely associated with each other. You can take advantage of this inter-connectedness to measure and learn to influence your physiology and psychology, resulting in significant improvements in wellbeing and performance. Before we delve into that process, we’ll explore some more of the physiology of stress and performance.

Rest & digest, fight or flight

Even the anticipation of a challenge can provoke a powerful physiological response which can see pulse rate and blood pressure soar. Feeling your heart pounding and beads of sweat forming on your forehead doesn’t feel great. These effects are not unsurprising, given that physiological and emotional states are closely associated with each-other

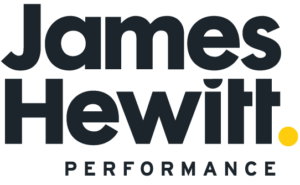

Physiological processes are regulated without conscious control by the ‘autonomic nervous system’. These processes include:

- Blood pressure

- Heart and breathing rates

- Body temperature

- Digestion

- Metabolism

- The balance of water and electrolytes (e.g. sodium and calcium)

- The production of body fluids (e.g. saliva, sweat, and tears)

- Urination and defecation

The autonomic nervous system is subdivided into two branches:

- The sympathetic nervous system (governs your ‘fight or flight’ stress response).

- The parasympathetic nervous system (governs your ‘rest and digest’ relaxation and recovery response).

The sympathetic nervous system consists of many nerves which drive physiological activation in the body. It’s responsible for the increased heart and breathing rate, sweaty palms and ‘butterflies’ in your stomach before an important event. You can imagine the sympathetic nervous system as the gas pedal on a car which revs up your internal engine and accelerates your activation.

Your fight or flight response can not shut off on its own

The sympathetic nervous system can not shut off on its own. The role of the parasympathetic nervous system is to act as a brake pedal in the process, slowing down heart rate, breathing, and relaxing your muscles. The principal components of the parasympathetic nervous system are a pair of cranial nerves (nerves which emerge directly from the brain), known as the vagus, or ‘vagal’ nerve. The vagal nerve is the longest in the autonomic nervous system. It connects the parasympathetic nervous system with the heart, lungs and digestive tract. The vagal nerve fibres run from your neck down to your hip, connecting with every organ, except for the adrenal glands. The vagal nerve also provides a bi-directional connection between the parasympathetic nervous system, and areas of the prefrontal cortex (the front part of your brain), which play an essential role in the regulation of emotions and behaviour.

Discovering ‘optimal activation’

In an ideal world, the sympathetic nervous system accelerates your activation until it reaches an optimal level. At this point, the parasympathetic nervous system applies the brakes, to keep it there. However, this is not always the case. As described earlier, sometimes we can be under-activated for a scenario. Still, often we find that we are over-activated, the sympathetic nervous system keeps accelerating, and the parasympathetic nervous system brakes are not strong enough to slow the process down; an experience we interpret as feeling ‘too stressed’.

Lessons from high performers

Some people might be more predisposed to be able to perform under pressure, but everyone can get better. Here are five steps you can take to prepare to perform at your best, whatever life throws at you.

1. Notice

It’s natural to feel stressed or excited in high-pressure situations, but creating space to up-regulate your awareness and pay attention to what you are thinking and how you are feeling can help to prepare you to perform at your best. When you face a high-pressure situation, start by trying to name two or three of your thoughts or emotions without judging them. This simple step creates a space between the stimulus and our response.

A famous quote describes this concept with great elegance.

“Between stimulus and response, there is space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.”

As a brief aside, while this quote is often attributed to Viktor E. Frankl, it does not appear in any of his writings. More likely, it seems, the phrase was popularised by the author, Stephen R. Covey. It’s understood that he discovered the quote (he can’t remember where), and felt that it beautifully articulated the thoughts of Viktor E. Frankl.

Whatever the case, the quote resonates deeply with many people, as it highlights several important aspects of the human experience. We do have a choice about how to respond, but we can quickly get out of the habit of taking the opportunity to make this choice. Mainly when we are in a high-pressure situation, pausing for a moment, to non-judgementally name a few thoughts or emotions, can be an effective tactic to rectify that mistake.

2. Manage

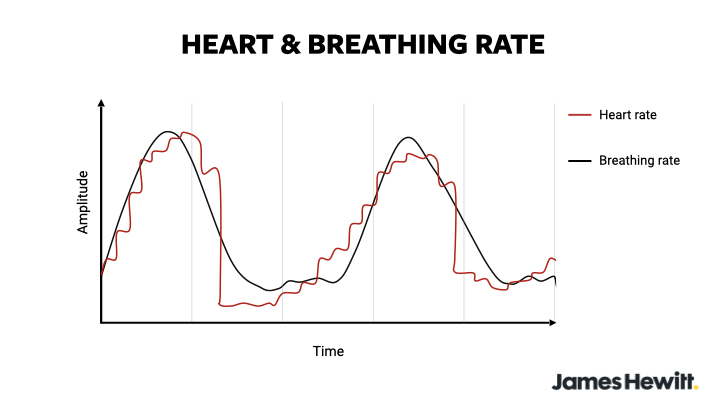

If you notice that you are concerned about a particular aspect of your performance, or if you’re feeling nervous, you can improve your ability to adapt to the challenge, or to the stressful situation, by adjusting your breathing rate. When we breathe in:- Contraction and downward movement of the diaphragm expands and reduces pressure in the chest cavity.

- The lungs expand, pressure decreases in the lungs, and air flows in.

- The atrium (upper chamber) of the heart expands more, pressure decreases in the atrium, and blood flow to the heart (venous return) increases.

- The increased expansion of the atrium, reduction in pressure, and increase in blood flow to the atrium increase the activity of baroreceptors (pressure sensors) in the heart.

- In response, baroreceptors suppress vagal nerve activity (i.e. reduce the pressure of the ‘foot’ on the parasympathetic brake).

- This reduction in vagal nerve activity (sometimes called vagal tone) increases heart rate.

- Relaxation and upward movement of the diaphragm contracts and increases pressure in the chest cavity.

- The lungs contract, pressure increases in the lungs, and air flows out.

- The atrium (upper chamber) of the heart expands less, pressure increases in the atrium, and blood flow to the heart (venous return) decreases.

- The decreased expansion of the atrium, increase in pressure, and decrease in blood flow to the atrium reduces the activity of baroreceptors (pressure sensors) in the heart.

- In response, baroreceptors relieve their suppression of vagal nerve activity (i.e. allow the foot to press back down on the parasympathetic brake).

- This increase in vagal nerve activity decreases heart rate.

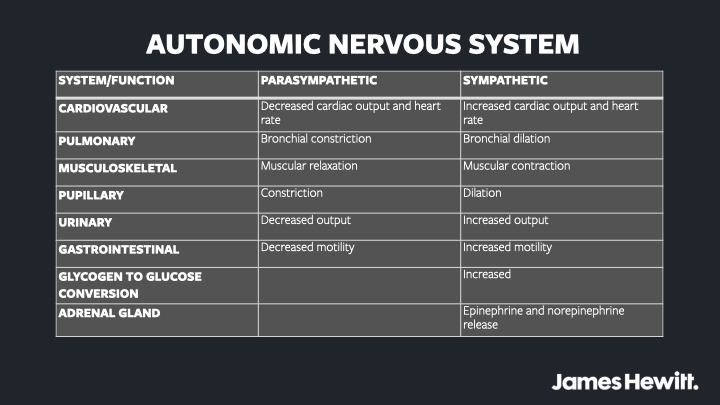

Why high-heart rate variability is generally better

While heart rate may appear to be steady when it is averaged over a minute, the time between each heartbeat is, in fact, continually changing. The difference in time between each heartbeat can be measured as heart rate variability. Higher heart rate variability is associated with a greater ability of the parasympathetic nervous system to adapt to changes, which in turn is related to improved health and resilience.

The sympathetic nervous system is always trying to accelerate. Having high heart rate variability is like having a skilled driver at the wheel who can apply the brake in just the right place, at just the right time, with the perfect amount of pressure on the pedal.

3. Focus

Given the fact that the vagal nerve fibres connect almost every organ, including areas of the prefrontal cortex (the front part of your brain), it’s perhaps unsurprising that high HRV is associated with several abilities related to prefrontal cortex activity. High HRV is associated with improvements in:

- Regulating activation of the fight-or-flight response of another region of the brain, called the amygdala2 (read more about stress and the amygdala)

- Regulating memory retrieval3.

- Working memory 3

- Sustained attention, situational awareness, and goal-directed behaviour3

Our attention is like a spotlight. We are never really not paying attention; it’s just a question of whether we are paying attention to the right thing, at the right time. However, when we focus on something in particular, it seems to change the electrical activity in parts of the brain cortex that represent the stimulus to which we are paying attention. Neurons in that part of the cortex stop signalling in synchrony4,5, and this may make individual neurons better able to respond to specific stimuli6.

In this step, after you have controlled your breathing at around six breaths per minute, try to activate your focus by bringing to mind one useful thought which will help you to move your attention back onto the task in front of you. For example, it could be focussing on just your opening sentence before a presentation. But make sure you decide on the one useful idea you will focus on ahead of time.

4. Perform

At this point, as the advert says, just do it. But most importantly, move your attention on to the process of your performance, not the outcome. Commit yourself, ahead of time, that you will choose to focus only on what you control. This means accepting that other factors, such as other people’s opinions, and even results will take care of themselves, providing you put in your best effort in the circumstances, whatever they are.

5. Feedback

Performing under pressure is a skill that we can all keep learning and improving on, and feedback is a crucial part of this. After your performance, ask someone you trust two questions:

- What did I do well?

- What could I work on?

Learning to perform under pressure is all about progress, not aiming for perfection. Try to put these five steps into practice next time you are facing a challenge. You might surprise yourself with what you’re capable of.

References

- Steffen PR, Austin T, DeBarros A, Brown T. The Impact of Resonance Frequency Breathing on Measures of Heart Rate Variability, Blood Pressure, and Mood. Front Public Heal. 2017;5(August):6–11.

- Thayer JF, Åhs F, Fredrikson M, Sollers JJ, Wager TD. A meta-analysis of heart rate variability and neuroimaging studies: Implications for heart rate variability as a marker of stress and health. Neurosci Biobehav Rev [Internet]. 2012;36(2):747–56. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.11.009

- Gillie BL, Vasey MW, Thayer JF. Heart Rate Variability Predicts Control Over Memory Retrieval. Psychol Sci. 2014;25(2):458–65.

- Thiele A, Bellgrove MA. Neuromodulation of Attention. Neuron [Internet]. 2018;97(4):769–85. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2018.01.008

- Harris KD, Thiele A. Cortical State and Attention Kenneth. Nat Rev Neurosci [Internet]. 2011;12:509–23. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3624763/pdf/nihms412728.pdf

- Waschke L, Tune S, Obleser J. Local cortical desynchronization and pupil-linked arousal differentially shape brain states for optimal sensory performance. Elife. 2019;8:1–27.