We are accelerating into the age of ‘connected everything’. There are almost three million apps in one of the world’s leading app stores, many of us check our smart-phones once every 6 minutes and most of us carry our digital devices for 22 hours per day.

In 1982, Blade Runner’s movie audience watched Deckard, played by Harrison Ford, chase androids through Los Angeles’ dystopian future. In a scene which likely felt very futuristic at the time, Deckard drops into a smoky bar to make a call on a videophone. Except for the smoky bar, the movie correctly anticipated several future trends, including the rise of video-calls.

Blade Runner’s storyline was set in 2019, the same year that video-conferencing software company ‘Zoom’ raised $356.8 million in its IPO. However, one development that Blade Runner failed to anticipate was the rise of ‘Zoom fatigue’, and the uniquely fatiguing nature of video calls.

There are several possible reasons for this, including:

- The need to focus more intently on conversations to absorb information, perhaps because of connection quality or sound issues, but also because we can’t quickly or easily seek clarification without using another interface (a chat window), or interrupting the whole conversation.

- With our screens open in front of us, new notifications are literally right in front of our face, vying for our intention, which can make resisting distraction more challenging.

- It’s too easy to fall into the trap of multitasking, by working on other tasks, such as reading and replying to an e-mail when we feel that there is a lull in the conversation; for example. These factors combine and contribute to our growing sense of tiredness from, and even dread of the next video calls.

Sometimes I wonder. While connectivity often seems limitless, and the choice of what we can consume in the digital realm is copious, are we truly experts in the use of our digital tools, or are we merely familiar? Are the rapid switches, scans and swipes which characterise our interactions with technology masking the fact that we have not truly mastered them, or realised their full potential and are we compromising our wellbeing and performance in the process?

Every revolution in technology has brought challenges and opportunities, requiring humans to make difficult decisions and complex judgments. We live and work as part of a wider system, but where previous transformations have impacted technology, our economy and society in a linear manner, the pervasiveness, independence and interconnectedness of the digital technologies are accelerating development at an exponential rate (source).

From a fixed to a flow based economy

Much of our consumption has shifted from ownership to access and our economy has moved from being based on fixed items to ‘flows’. For example, the newspaper, a medium fixed by its limited number of pages, is experiencing global declines in circulation across publications. 86% of people are more likely to use Twitter as their principle source of news, browsing feeds from various sources continuously. We do not purchase CDs or listen to hour-long albums, we stream music for as long as we want to using services such as Spotify. We rarely post letters, but likely spend up to 60% of our day in some form of electronic communication.

While digitization and flows have increased availability and choice, they have also multiplied complexity, uncertainty and behaviour has become more orientated toward the short-term.

Variety overload

Our brains are not predisposed to meet the demands of the highly specialised tasks and efforts required by modern digital society. We attempt to cope by ‘multi-tasking’, but this approach can cannibalise up to 40% of productive time (source). We make more mistakes, learn less and tasks take longer to complete.

Combining two effortful tasks is harder than completing them separately. Switching tasks increases cognitive load. Most of what we call multi-tasking is actually the prefrontal cortex – a region toward the front of our brain – acting as a policeman directing traffic at a busy intersection, switching between the various neural networks required for the flow of processes associated with each task.

Our smartphones buzz with notifications throughout the day and night; we accept relentless distraction as the default option. Habitual checking on missed calls and messages can become an addictive pattern of behaviour, increasing stress and disturbing sleep. More than 90% of people multi-task during meetings. 42% of us admit to reading and responding to e-mail in the bathroom. 70% of us check e-mail while watching TV. When we find the opportunity to rest, 34% of us admit to using social media as a form of mental break. However, while it may activate our reward mechanisms, these diversions do not restore us. They are another form of ‘pseudo work’ for our brains as we switch and process content.

Even if our devices are switched off, cognitive capacity is significantly reduced when our smartphone is within reach.

Ward et al. (2017) Brain Drain: The Mere Presence of One’s Own Smartphone Reduces Available Cognitive Capacity.

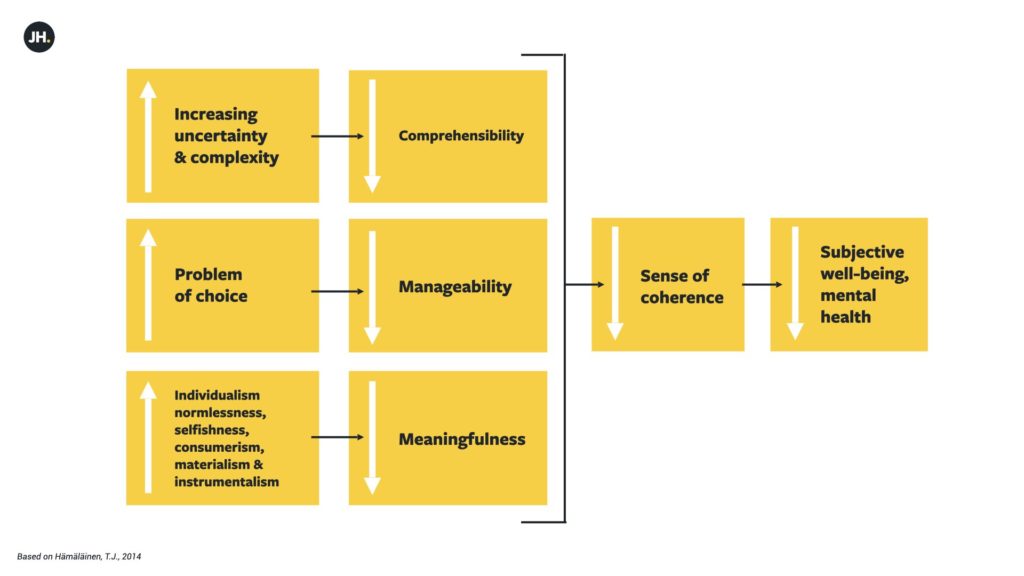

It can feel like there is an incoherence between the demands that our environment makes of us, and our ability to meet these demands. This may go some way to explaining why an abundance of information and choice has not necessarily been accompanied by a growing sense of wellbeing. Many of us feel that everyday life is no longer under our control. We have a variety overload. The more activities we choose to engage in, the less time and energy we have for each of them.

Socio-economic transformation & wellbeing

Familiarity is not expertise

With hindsight, we may reflect on the emergence of the world-wide-web and global digitalisation as the greatest technological development our species experienced since the emergence of language. Perhaps there are similarities between these advances: Language is a massive, interlocking toolset. It can be disassembled, reassembled, aggregated and combined to create many things. As language developed and humanity assembled words into increasingly complex structures it appeared useful to agree on structures and relationships between words, in order to maximise their usefulness.

In isolation, a word is a tool, but its potential is truly realised when it is combined with others into an assembly, a technology, which can efficiently perform a given task. Paradoxically, if we had never introduced limits and agreed structures to govern our use of words, we would have limited their creative potential. With language, we accept that limitless choice is actually a limiter.

Structuring our flows

In contrast, we look for ever-increasing ways to embed digital flows into every moment of our day. WiFi on planes, cellular connections on our wrists and the emergence of augmented reality infuse every experience with more data. There are few structures or norms in our flow-based approach to using digital tools. We navigate our digital universe by continuously disassembling, reassembling, aggregating and combining in limitless configurations.

We are very familiar and have an ever-growing vocabulary of options available to us, but without any structure guiding our use, are we diminishing the value and potential inherent in these powerful tools? We may feel productive and efficient, but we often make our lives more difficult than they need to be. Like words improperly arranged, our communication and creativity is restricted, becomes more effortful and frustrating that it could be. Do we need to accept that some limits to our digital experience may be beneficial?

A case for organisation & limiting choice

Our digital tools will not impose boundaries for us. Unless we choose to create limits, our attention will continue to be harvested to the point of exhaustion. Perhaps we need to move beyond familiarity and begin to establish new frameworks; a grammar for the digital age which promotes enhanced wellbeing and more sustainable performance to release the full spectrum of possibility available to us.

These frameworks could begin in very simple ways. Reducing the number of times we check our e-mail to three times per day, as opposed to as often as we can, is associated with significant reductions in stress. People who move their phone to another room significantly outperform those who leave their phone on their desk in assessments of cognitive performance.

A new language for technology

The purpose of these new structures should be to direct and shape the ‘flows’ associated with our use of digital tools. In my work I often suggest that clients begin with three simple adaptations of existing linguistic approaches:

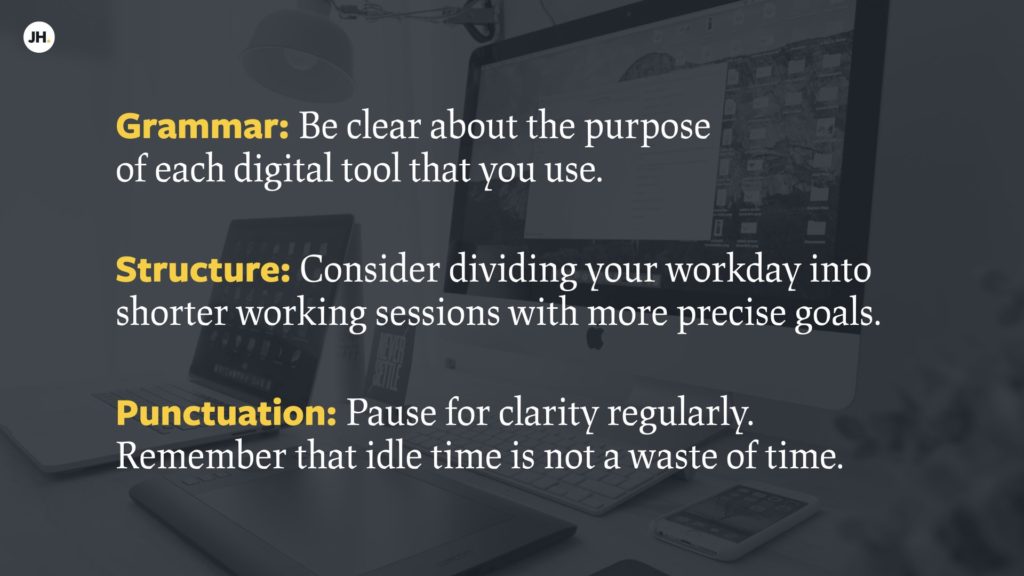

- Grammar: Be clear about the purpose of each digital tool that you use. As with words, there may be multiple uses for the same tool, but trying to apply multiple purposes at once is confusing & less effective. Also, consider that just because you can use a tool doesn’t necessarily mean that you should.

- Structure: As with sentences and paragraphs, sequence your use of digital tools, rather than interweaving continuously. Consider dividing your workday into shorter working sessions with more precise goals and careful selection of the most appropriate tool.

- Punctuation: Pause for clarity regularly and enjoy some disconnected time. Don’t rely on self-control. Consider switching-off your devices and/or putting them out of sight. Remember that idle time is not a waste of time.

These new norms will take time to develop and become established, but we have a sophisticated cognitive control system. Human beings have proven able to adapt to a wide variety of demands. Initially, it may feel burdensome, just it is does when we seek to master a new language, but in time, the basic rules which underpin optimum use of our digital tools may become automatized and less effortful as we pause more regularly, enhance clarity, reduce effort, stress, improve learning and interact with technology in more sophisticated and meaningful ways, making better use of the incredible array of tools we have available to us.